*Pour lire cet article en français

When

I tell friends that I conduct research at the Smithsonian, most think

immediately of Washington. Fellow students and I are currently enrolled

in a tropical biology field course at the Smithsonian... in Panamá, not

not on the Potomac shoreline! So let’s make things clear with a quick

overview (i.e. publicity shpiel) of STRI, one of the world’s flagships

of tropical research.

The

Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) is a community of

researchers and scholars interested in the tropics. It is part of the

Smithsonian Institution network and hosts 40 permanent scientists, 400

support staff and 1,400 visiting scientists and students. My colleagues

and I, all graduate students of the University of Illinois at

Urbana-Champaign, the Instituto de Investigaciones Científicas y Servicios de Alta Tecnología (INDICASAT) and McGill University’s NEO program, are part of this community.

Together,

we seek to understand the tropics, in all their complexity, and merge

our diverse areas of expertise to do so. According to STRI’s Scientist

Emeritus, Egbert Leigh Jr., most of STRI’s research can be grouped under

12 broad areas. First, we seek to contrast and compare two oceans, the

Pacific and the Atlantic, and understand how they came to be so

different. We try to accumulate as much data as possible on the recent

past, to understand what is happening today in both the human and

natural worlds. We seek to understand the distant past through

archaeology, and learn how our world came to be. We try to uncover why

and how individuals diverge within a species to give rise to more

species. We try to unravel the mysteries of mutualism, or why some

species collaborate with each other while others prefer to cheat. We

study social behaviour in animals, but also in humans within the Central

American context. We want to understand what natural selection favors

and why some traits make it to the next generation while others do not.

We study the factors regulating populations of living organisms and the

inner workings of food webs. We look at how species (humans included)

cope with extremes (light, shade, drought, floods, lousy soils, etc.).

We try to understand how so many species can coexist in a single place

(900 species of birds in Panamá and around 300 tree species in 50

hectares of forest). We are definitely interested by a lingering

question... why so many tropical trees (and why is their identification

such a hellish job)? Finally, we want to get a global picture of

tropical systems by unravelling the interdependencies that make

ecosystems go-round.

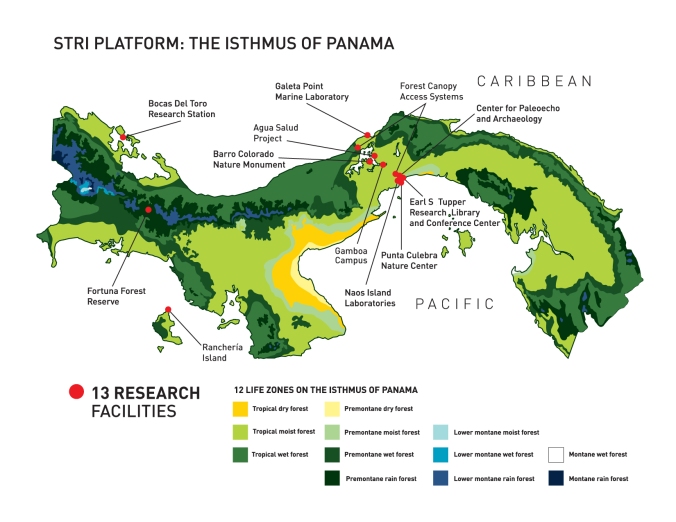

Enough

about questions, we need answers! Good research is backed by good

infrastructure. Luckily for us, you can’t really beat STRI. We have

access to 13 research facilities across the Isthmus of Panamá and here’s

a very brief description of each.

A map of all STRI research facilities in Panamá (Credit: STRI, http://stri.si.edu/reu/english/why_panama.php).

1) Earl S. Tupper Research, Library and Conference Center

This

set of buildings hosts most of the administrative units, a score of

laboratories equipped for all kinds of research, a herbarium, an insect

collection and a library comprising over 69,000 volumes centered on

tropical sciences. The old and rare books section is to die for... if

you like getting your hands on the drawings of 17th to 19th century

explorers.

The Earl S. Tupper Library holds over 69,000 volumes related to tropical sciences (Photo: Nicolas Chatel-Launay).

2) Center for Tropical Paleoecology and Archaeology (CTPA)

If

you dig fossils, that’s the place you want to be. Specialized in

geology, geography and archaeology, scientists working here try to

unravel the distant past, from giant (and thankfully extinct) snake

species to the processes that explain why North and South America became

one land mass three million years ago. Scientists from CTPA are

currently using the Canal expansion project as a way to dig further into

Panama’s past.

3) NAOS Island Laboratories

Located

at the Pacific entrance of the Canal, this research facility has a

state of the art molecular and genetics laboratory. It also has all you

need to keep oceanic critters alive for research. People here specialise

in Pacific oceanography and paleontology.

4) Galeta Point Marine Laboratory

NAOS’s

counterpart, this research facility is located at the Caribbean

entrance of the Canal. It is best known for research on the effects of

oil spills and on mangrove systems.

A view of one of the numerous coral reefs neighboring the Bocas Del Toro Research Station (Photo: Nicolas Chatel-Launay).

5) Bocas Del Toro Research Station

Located

in the Bocas Del Toro Archipelago, this station hosts scientists who

work on coral reefs, lagoon systems and lowland tropical forests. As it

is located on the Caribbean side, in the middle of a cultural melting

pot between Asia, Africa and the Americas, it is also a research hub on

human sociality.

6) Rancheria Island

Located

on a Pacific Island, this research station is in the middle of the

Eastern Pacific Ocean’s largest concentration of coral reefs. It is the

Pacific counterpart of Bocas Del Toro.

7) Punta Culebra Nature Center

Located

on a Pacific Island, this center focuses on public awareness and

outreach. Scientists try to test education strategies in order to better

transmit knowledge to the coming generations.

The Fortuna Forest Reserve lets scientists work in a unique ecosystem... cloud forest (Photo: Nicolas Chatel-Launay).

8) Fortuna Field Station

Fortuna

Forest Reserve is 1,200 meters (4,000 feet) up in the mountains and

lets scientists study a particularly interesting tropical ecosystem... a

cloud forest. I can tell you that the sun is rare out there, and it’s

constantly wet. Some areas of the reserve receive 12 meters of rain a

year (and have less than 30 rain-free days yearly).

A clear night sky in Fortuna is a rare event, less than 30 days a year are rainless (Photo: Nicolas Chatel-Launay).

9) Agua Salud

This

project, located within the Panamá Canal watershed covers 300,000

hectares. Scientists involved in this long-term study try to test the

best reforestation strategies and how different techniques can be used

to store carbon, control devastating floods, or improve soil

fertility... all without banning agriculture. People here try to get to

an optimal land-use strategy for the tropics.

10) Forest Canopy Access Systems

People

at STRI are all smart. But some have exceptionally smart ideas. Two

construction cranes were permanently installed in the rainforest on both

the Pacific and Caribbean sides so that scientists could easily access

the forest canopy. Wonder how we could get this close to a mommy sloth

and its baby in the posts from Scott, Librada and Flor? Yup, we were in a crane.

11) Gamboa Campus

Here

we are! this is the main base our group used for the Tropical Biology

Field Course 2015. Gamboa Campus is located at the dead center of the

Panamá Canal, and has a suite of laboratories. Also, a lot of

specialized research happens here. There is a system of “pods” to grow

plants in different temperature and atmospheric conditions to unravel

the effects climate change might have in the tropics. There are flight

cages that bats call home and where their behaviour is finely analyzed.

And there is Pipeline road, a well-known spot for anyone interested in

birds (See Elise’s post on the IGERT-NEO blog).

Among all our activities in Gamboa, bat trapping was certainly one of the most interesting (Photo: Nicolas Chatel-Launay).

12) Barro Colorado Nature Monument (BCI)

The

Crown Jewel! Barro Colorado is an island, surrounded by three

peninsulas, all protected by the Panamanian government and the

Smithsonian Institution. Only research can go on here. With its 5,400

hectares, it is the oldest STRI facility, first occupied in 1924. The

island itself is a no-touch zone. You can measure and observe, but you

can’t change anything. The peninsulas are used for experiments, as in...

what happens if you kill all lianas in a forest? Do the trees grow

better? Or again, what happens if you change the nutrient regimes by

dumping tons of fertilisers?

A view of the main buildings on BCI island (Photo: Nicolas Chatel-Launay).

13) Center for Tropical Forest Science (CTFS)

Located

on BCI Island and founded in 1980, this 50 hectares forest plot gave us

the most precious data set ever collected in tropical biology. Every

single tree stem larger than 1 cm (there are roughly 200,000 of them),

is identified to species, measured, and recensused every five years. The

same goes for lianas, and many groups of shrubs. We also have precise

soil composition data all over the plot. We have mammal, bird and insect

inventories for the area. Many mammals and birds even have radio

collars; we can track their every movement in the forest. Basically, we

can have lots of fun with lots of data. Not only is the 50-hectare plot

an awesome dataset, it had children. CTFS plots are now all over the

Americas, Africa, Asia, Europe, and Oceania. People there collect data

in the same manner, using the same protocol. This way, we can compare

forests through space and through time, precisely, individual by

individual, all over the world. Imagine what questions you can explore

with that.

So

here we are! This was a small overview of what we do, and where we do

it. STRI is composed of biologists, archaeologists, anthropologists,

geographers, and specialists of other fields trying to answer one

question. What makes the tropics tick? And if you’re jealous, well don’t

be. You are welcome to join in this adventure.

--

Nicolas Chatel-Launay

--

Nicolas Chatel-Launay

Mass Communication courses in Australia provide a platform for you to shine in your respective career choices. It gives you the requisite know how about the various

ReplyDeletetools of mass media.

research institute

In a venture to reinforce its support to academics and researchers, Asia-Pacific Institute of Advanced Research (APIAR)is pleased to inform you of a new agreement

ReplyDeleteto publish high-quality conference articles in the following two journals:

– International Journal of Web Based Communities (ISSN: 1741-8216)

– International Journal of Continuing Engineering Education and Life-Long Learning (ISSN: 1741-5055)

All conference articles from 1st Asia Pacific Conference on Contemporary Research (APCCR-2015) will be checked against the rigorous criteria set by these two

journals, and articles meeting the requirements will be published in special issues of the journals.

cutting-edge technology

PHP is one of the fastest growing web scripting languages on the Internet today, and for good reason.

ReplyDeletePHP (which stands for Hypertext Preprocessor) was designed explicitly for the web.

php